I was looking at a picture of a ladybug the other day, and I started thinking man, this little guy is just not very stylish. Ladybugs need a bit more variation in their wardrobes. And so I offer you the opportunity to dress your very own ladybug in some sartorially-conscious argyle:

Ok, so not really. I just like argyle, and I like ladybugs. I'll take you step-by-step through the process that I used to create this guy.

1. The first step is to collect the files that you'll be using. You can import them into Photoshop now, or just leave them in a handy place so that you can find them as the need arises. I used this ladybug from

this website:

|

| By LittleMissParasite |

This leaf from

here:

And the argyle pattern from

this tutorial (you could make your own in Illustrator - it's an excellent tutorial - but I used the final product that he posts on his website):

2. Once you've got your files assembled, open up Photoshop and create a new file. I'm using a canvas size of 1366x768 so that I can use it as a desktop background, but you can make yours any size you want (within reason - keep the resolution of the leaf and ladybug in mind). Import the ladybug file and give it its own layer. Title the layer something appropriate.

3. The next step is to extract the ladybug and leave the leaf behind. I suppose you could skip this step and just use the background as-is, but I found a leaf I liked more, and I didn't particularly like the border around the edges. For this particular extraction, I used the quick mask mode. You might be able to get away with using the magnetic lasso, but I didn't like the result. Your other option is the pen tool, but I think that the quick mask gives the best results - you just have to be a little bit patient.

Enter the quick mask mode by pressing "q" on the keyboard or selecting the circle-inside-a-rectangle icon below the foreground/background selection swatches.

Select a round brush with 100% hardness. Make sure that the flow and opacity are both set to 100%.

3. Double clicking on the click mask icon will bring up this window:

Use approximately these settings. The color is important - quick mask defaults to red, and a red mask on a red ladybug won't go very well. I also bumped the opacity up to 70%. I thought 50% was a little difficult to see.

4. Start painting over the ladybug with a fairly big brush. I started with a very large brush - 300 px or so - to cover the majority of the ladybug's shell.

5. Using progressively smaller brushes, start painting over the more detailed parts of the ladybug. A helpful keyboard shortcut here is using the "[" and "]" keys to change the size of the brush. Don't go too crazy - you can skip painting in the little hairs on the antennae, for example - but you do need to go pretty small to get the legs and stuff.

Zoom in for the finer details. The finer your work is here, the better the final product will look. Keep going until the entire ladybug is masked in blue.

This level of detail should be fine. For the last bit of masking, I switched back to a very large brush, and used the edge of that to approximate the curve of the ladybug's shell. That way, you get a smoother edge. (There's math there, I just don't know exactly what it is. Something calculus-y.)

6. Now press "q" again. The marching ants selection line should appear around everything that was not masked.

7. Now press "Delete". You should be left with just a ladybug on a white background. I resized and rotated it a bit using Transform (Ctrl+T), but you don't have to if you don't want to.

8. Now import your new leaf background on a different layer. Title it something impressively creative.

9. The next step is to put the leaf into perspective, so it looks like the ladybug is actually walking on the leaf and not floating in front of it. Press Ctrl+T to transform it, then hold down Ctrl to use the Distort mode as you move the handles as below. You may want to move the ladybug layer above the leaf layer for a reference.

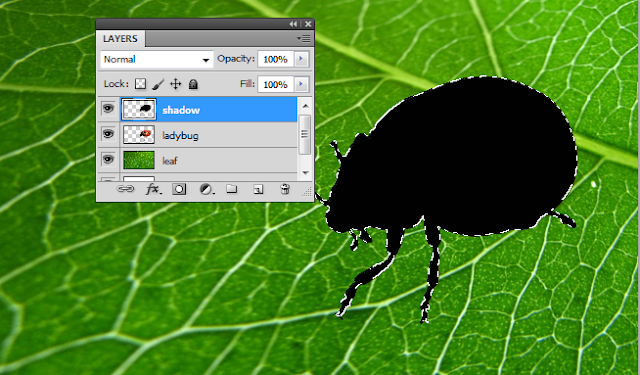

11. Obviously we've got some work to do here - it looks awfully Photoshop-y at this point. The first step is to add the ladybug's shadow back in. Press Ctrl and click on the ladybug thumbnail in the layers palette to select just the ladybug. Copy and paste it into its own layer and call that layer "shadow."

Now, with that shape still selected, fill it the selection with black.

12. Move the shadow layer under the ladybug layer. Get rid of the selection (Ctrl+D), but keep the shadow layer activated. Go to Filter>Blur>Gaussian Blur and set the blur to 13.0 px.

13. Using the direct selection tool (the black arrow symbol), move the shadow so that it approximates the original shadow in the original photo. No need to get too precise - we're going to transform it in the next step to make it look a little more accurate.

14. It looks better with the shadow, but the legs still look like they're floating a bit, and the overall shape isn't quite right. While you're still on the shadow layer, press Ctrl+T to transform it, then right click on the canvas and select the Warp tool.

15. Using the Warp tool, start nudging the shadow around. You want to make the shadow near the head a little bit wider. Also, make the shadow-feet meet up with the real feet in such a way that the feet touch, but the shadow of the leg is in front of the real leg.

16. Better, but still not perfect. Pick up the brush tool and select a round 0% hardness brush and set the opacity and flow as shown:

Now, brush in some shadows near the feet. Use a small brush (like 12 px to start), and as you move away from the foot, use one a few pixels larger - maybe 20 px. Don't go crazy - subtlety can work in your favor here. Let the shadow fade away as you move away from the foot.

Shadows can really make or break your image, so be careful in this step. Take the angle of the light into account, as well as the angle of the legs and the angle of the leaf. If you took a really long time to get this step right, it would be time well-spent.

17. Once you're happy with your shadow, it's time to move on to the interesting stuff. Import your argyle texture (or follow this

excellent tutorial and make your own) and give it its own layer above the ladybug.

18. Press Ctrl+T to transform the image, and rotate it clockwise about 45 degrees. I also resized it to be slightly smaller. Make sure that if you do resize it, you hold down the shift key to maintain the proportions.

You'll also notice that I took the opacity of the argyle down to about 70% to make it easier to line up the pattern. Try to line it up so that the line down the center of the carapace lies directly between two of the black diamonds. It will also look better if that line is parallel to the line that runs through the longest dimension of the black diamonds at at least one point. See below:

19. Still in Transform mode, select the Warp tool again. Start nudging the argyle shape around the ladybug's shell. The important parts are the top and bottom edges. See if you can make the argyle pattern make the same curve as those upper and lower edges. Don't worry if the pattern hangs over in some places. We'll crop that out later.

20. Hold Ctrl and click on the argyle layer thumbnail to select its contents. Go to Filter>Distort>Spherize, and set the slider to about 45%. Press OK.

21. Depending on how happy you are with the argyle pattern at this point, you may or may not need to go to the next step. Go to Filter>Liquefy and choose the Bloat tool.

With a these settings, click once or twice in the center of the argyle pattern.

You may find it necessary to go back now and redo some of the warping you did earlier. You can modify it all you like, but make sure that the argyle always overlaps all of the red.

22. Now turn off the argyle layer for the moment. Click on the ladybug layer and select the magnetic lasso tool (click and hold on the lasso tool to find it).

Using the magnetic lasso, trace all the way around the red part of the ladybug. The tool does a nice job of selecting anchor points itself, but sometimes you may need to click and add one if the tool wanders off in an odd direction. Once you've made it all the way around, click on your very first anchor point to complete the loop and make the selection.

23. Go back and turn your argyle layer back to visible and make sure that layer is active. Press Ctrl+Shift+I to invert the selection, then press Delete.

24. Turn up the opacity of the argyle layer to 100% and select Overlay as the blend mode (Soft Light and Linear Light might also work, depending on your preference).

25. Make a new layer on top of the argyle layer and fill it with this gradient:

Copy all of it (Ctrl+C). Go to the Channels palette and paste it into a new channel (Ctrl+V). Call this channel "blur source".

You can delete the original gradient at this point - we don't need it anymore.

26. In this step, you're going to have to combine all your current layers into one. I like to make a copy of all of them, just in case I have to go back and change something. Lock the duplicates and make them invisible.

Now select all of your other layers, right click, and select "Merge visible".

I forgot to take a screenshot of this, but using your rectangular marquee tool, select the entire canvas and copy it onto a new layer. You can get rid of the old merged layer. This will make it easier to apply an accurate Lens Blur in the next step.

27. With your new merged layer, go to Filter>Blur>Lens Blur. You can play around with the settings to find a look that you like. I like these settings:

Make sure that the source is set as "blur source" (or whatever you titled your gradient in the channels palette). I have the shape set to octagonal, the radius to 19, the curvature at 8, and the rotation at 31.

28. Last step: vignetting. No doubt there are real graphic designers out there going "God no! Not another vignette!", but I like the way it looks. Go to Filter>Lens Correction and apply these settings:

That's it! I didn't quite like the way the argyle pattern lined up with the shell, so I went back and changed the way it was warped back before the Spherize and Bloat steps. Here's my final result:

Questions? Leave a comment!

If you use this tutorial and happen to post your result somewhere on the interwebs, leave a link...I'd love to see!